Are you a small city with a population of 3,000 or fewer?

Are you dreaming of growth and development, and a brighter future?

The Rural Capacity Program is your opportunity to turn those dreams into reality!

Why should you apply? Because your city will receive support, resources, and expertise from CEDA to help you achieve your goals thanks to a special appropriation from the State of Minnesota. This includes:

- Up to 135 hours of Technical Assistance: Covered by a special appropriation from the State of Minnesota, along with up to $13,500 CASH in the form of a grant to your city to help implement your program.

- Expert Guidance: CEDA’s team of professionals will work hand-in-hand with your city to create a tailored plan that meets your unique needs.

- Proven Success: CEDA has a proven track record of helping small cities like yours thrive and prosper.

- Strong Community Partnerships: CEDA collaborates with local businesses, organizations, and government agencies to maximize the impact of our programs.

CEDA’s tailored programs are dedicated to addressing the specific challenges faced by small communities like yours. CEDA will work with your city to develop and implement a tailored program that specifically addresses your city’s needs and fits into one of the categories below:

Revolving Loan Funds: Jumpstart your local economy by offering low-interest, gap financing designed to support entrepreneurs looking to start or expand their businesses. Our expert team will guide you through the complex world of creditworthiness, finance and loan administration.

Commercial Exterior Improvement Grants/Loans: Enhance the beauty and vitality of your community by developing grants and loans. Whether it’s sprucing up a specific area or beautifying the entire community, we can help you develop a program unique to your city’s needs.

Business Incubation Programs: We know that nurturing new businesses is essential for growth. Our flexible incubation programs can help you offer rental subsidies, technical assistance, and educational support, making it easier for potential and new entrepreneurs to flourish.

Childcare Incentive Programs: Ensure a brighter future for your youngest residents by supporting existing or new childcare providers. The program we’ve developed assists with licensure fees and continuing education, promoting increased capacity and higher-quality care.

Business Retention and Expansion Program: Building a strong local economy starts with understanding your businesses. Our program facilitates meaningful conversations with local businesses, helping you identify challenges, prioritize solutions, and seize new opportunities for growth.

Rural cities with limited staff, budget, and economic development experience are encouraged to apply. The purpose of this special appropriation from the State of Minnesota is to help the smallest and most rural cities in Minnesota take advantage of economic development opportunities in their communities! You do not need to have an EDA to apply. CEDA will make every effort to equally distribute grant awards throughout Greater Minnesota.

Deadline for applications is December 1, 2025.

Contact CEDA with any questions. 507-867-3164 or email amy.schaefer@cedausa.com

Theresa Bentz of Get Bentz Farm builds an interactive agricultural experience in the hills outside Northfield. Grass-fed

Theresa Bentz of Get Bentz Farm builds an interactive agricultural experience in the hills outside Northfield. Grass-fed sheep battle invasive species, on-farm fiber art days encourage community, discard wool becomes garden food and two city kids experiment daily with their hypothesis about a different way to live and work.

sheep battle invasive species, on-farm fiber art days encourage community, discard wool becomes garden food and two city kids experiment daily with their hypothesis about a different way to live and work. At the start, the farm focused on pasture-raised direct-to-consumer sheep and lamb meat sold at farmers markets. They raise their flock following sustainable practices of rotating pastures and allowing the sheep to browse a diverse array of plants. Their lamb is regularly on Northfield’s Ole Store’s menu, including custom lamb brats.

At the start, the farm focused on pasture-raised direct-to-consumer sheep and lamb meat sold at farmers markets. They raise their flock following sustainable practices of rotating pastures and allowing the sheep to browse a diverse array of plants. Their lamb is regularly on Northfield’s Ole Store’s menu, including custom lamb brats.

As the baroness of Get Bentz Farm, Theresa uses both wool from her flock and fleece purchased from shepherds throughout the region to create her signature products. “I love that I’ve become a producer of yarn in our industry,” smiles Theresa. “I enjoy having control over the end product. I get to collaborate with others to create something that

As the baroness of Get Bentz Farm, Theresa uses both wool from her flock and fleece purchased from shepherds throughout the region to create her signature products. “I love that I’ve become a producer of yarn in our industry,” smiles Theresa. “I enjoy having control over the end product. I get to collaborate with others to create something that  people use.”

people use.” Get Bentz is a graduate of the 2024 cohort of the Rural Business Innovation Lab. Founded by CEDA, RBIL is a cohort-based, entrepreneurial program that redefines the narrative of rural decline. Each cohort builds a peer network dense with ideas, expertise and resources that help rural small businesses start and scale their work within their communities. Working in both Minnesota and Wisconsin, RBIL supports rural businesses in their growth to become sustainable drivers of economic health.

Get Bentz is a graduate of the 2024 cohort of the Rural Business Innovation Lab. Founded by CEDA, RBIL is a cohort-based, entrepreneurial program that redefines the narrative of rural decline. Each cohort builds a peer network dense with ideas, expertise and resources that help rural small businesses start and scale their work within their communities. Working in both Minnesota and Wisconsin, RBIL supports rural businesses in their growth to become sustainable drivers of economic health. importantly, what she did not want to do during a big year of growth for their farm business. “The coaches at RBIL helped me push myself into areas where I didn’t think I was going to be comfortable,” says Theresa. “I bought a Yamper because we identified that I didn’t have a good place to sell my yarn on the farm. It’s turned out to be really fun. Our yarn camper is a mobile yarn mobile. We now are able to participate in events where we wouldn’t have otherwise because of building this mobile interactive space.”

importantly, what she did not want to do during a big year of growth for their farm business. “The coaches at RBIL helped me push myself into areas where I didn’t think I was going to be comfortable,” says Theresa. “I bought a Yamper because we identified that I didn’t have a good place to sell my yarn on the farm. It’s turned out to be really fun. Our yarn camper is a mobile yarn mobile. We now are able to participate in events where we wouldn’t have otherwise because of building this mobile interactive space.” Sign up for the monthly Get Bentz newsletter, which includes the perspective of the flock itself, at

Sign up for the monthly Get Bentz newsletter, which includes the perspective of the flock itself, at  Follow Meet the Minnesota Makers @meettheminnesotamakers on Ambit, Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn.

Follow Meet the Minnesota Makers @meettheminnesotamakers on Ambit, Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn. Minnesota soil turns out to have just the right qualities for growing high-quality ginseng.

Minnesota soil turns out to have just the right qualities for growing high-quality ginseng.

Tyler started working with ginseng by going out into the woods each fall with his grandfather to transplant roots and select which ones to harvest. Tyler learned how to clean and dry the roots to prepare them for sale—often to destinations in New York City and San Francisco.

Tyler started working with ginseng by going out into the woods each fall with his grandfather to transplant roots and select which ones to harvest. Tyler learned how to clean and dry the roots to prepare them for sale—often to destinations in New York City and San Francisco. since educating market visitors about ginseng and sharing their harvest in both whole roots and ground powdered form.

since educating market visitors about ginseng and sharing their harvest in both whole roots and ground powdered form. Roots are typically at least six years old before being dried and processed into powder, the most typical way that people use the prized root. The longer it grows, the stronger its potency. Ginseng plants thrive in shaded conditions, making them an ideal agroforestry crop. A drought resistant plant, dry summers make for steady growing conditions. Winters without snow cover, however, pose a challenge as turkeys and other critters dig up the plants.

Roots are typically at least six years old before being dried and processed into powder, the most typical way that people use the prized root. The longer it grows, the stronger its potency. Ginseng plants thrive in shaded conditions, making them an ideal agroforestry crop. A drought resistant plant, dry summers make for steady growing conditions. Winters without snow cover, however, pose a challenge as turkeys and other critters dig up the plants.

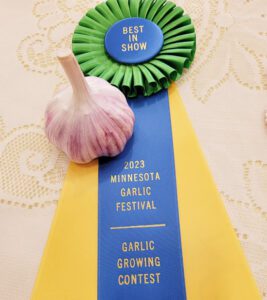

The garlic lifestyle is the cornerstone of the Olberding Family’s Rustic Roots Farm in Alexandria, Minnesota.

The garlic lifestyle is the cornerstone of the Olberding Family’s Rustic Roots Farm in Alexandria, Minnesota. syrup, planted asparagus, powdered garlic to reduce food waste, established mushroom logs, built a farm stand, and created custom spice blends using their garlic powders.

syrup, planted asparagus, powdered garlic to reduce food waste, established mushroom logs, built a farm stand, and created custom spice blends using their garlic powders.

entrepreneurial program that redefines the narrative of rural decline. Each cohort builds a peer network dense with ideas, expertise, and resources that help rural small businesses start and scale their work within their communities. Working in both Minnesota and Wisconsin, RBIL supports rural businesses in their growth to become sustainable drivers of economic health.

entrepreneurial program that redefines the narrative of rural decline. Each cohort builds a peer network dense with ideas, expertise, and resources that help rural small businesses start and scale their work within their communities. Working in both Minnesota and Wisconsin, RBIL supports rural businesses in their growth to become sustainable drivers of economic health. The program tailors itself to fit a range of business types including farms with value-added products that depend on direct-to-consumer sales like Rustic Roots. “I know we accomplished a lot more in this past year than we would have if it was just us doing it on our own,” shares Julie. “Having guidance from our coaches and professional experts is so helpful. The networking of our peers continues to be incredible. We’re all in the weeds together. It offsets the isolation of running your own business where everything can simply feel so hard.”

The program tailors itself to fit a range of business types including farms with value-added products that depend on direct-to-consumer sales like Rustic Roots. “I know we accomplished a lot more in this past year than we would have if it was just us doing it on our own,” shares Julie. “Having guidance from our coaches and professional experts is so helpful. The networking of our peers continues to be incredible. We’re all in the weeds together. It offsets the isolation of running your own business where everything can simply feel so hard.” Sign up for their newsletter at

Sign up for their newsletter at  On a gentle slope in southern Minnesota that Rachel Davis’ grandparents called Poverty Knob, Kalvin, Rachel and their children raise a myriad of mushrooms at their ten acre certified organic solar-powered farm. Now the fourth generation to steward the land, their innovations in sustainable practices make year round fresh produce feasible in a responsible fashion.

On a gentle slope in southern Minnesota that Rachel Davis’ grandparents called Poverty Knob, Kalvin, Rachel and their children raise a myriad of mushrooms at their ten acre certified organic solar-powered farm. Now the fourth generation to steward the land, their innovations in sustainable practices make year round fresh produce feasible in a responsible fashion. LeRoy, a town of approximately 900, coming home offered an opportunity to build their dream life within their community.

LeRoy, a town of approximately 900, coming home offered an opportunity to build their dream life within their community. Kalvin, a trained carpenter, converted the farm’s garage into an insulated production space for 150-200 pounds of mushrooms weekly. Their outdoor forest farming space provides fertile growing space for more mushrooms, ferns and art installations.

Kalvin, a trained carpenter, converted the farm’s garage into an insulated production space for 150-200 pounds of mushrooms weekly. Their outdoor forest farming space provides fertile growing space for more mushrooms, ferns and art installations.

“We were really excited about the prospect of having personalized coaches to help our business scale up. RBIL helped us to achieve so much more than we initially had thought we would get out of this experience.”

“We were really excited about the prospect of having personalized coaches to help our business scale up. RBIL helped us to achieve so much more than we initially had thought we would get out of this experience.” Kalvin’s personal favorite mushroom that they grow is their chestnut. Gently fried, it adds a delightful crunch on top of a Ramen bowl. “It gives a squid or calamari vibe,” says Kalvin. His favorite to forage is hen of the woods. Kalvin describes it as the chicken leg as opposed to the chicken breast-like flavor found in the colorful chicken of the woods mushroom. “The best way to prepare hen of the woods is deep fried in a beer batter with a side of garlic aioli. It may not be the healthiest, but it’s so good.”

Kalvin’s personal favorite mushroom that they grow is their chestnut. Gently fried, it adds a delightful crunch on top of a Ramen bowl. “It gives a squid or calamari vibe,” says Kalvin. His favorite to forage is hen of the woods. Kalvin describes it as the chicken leg as opposed to the chicken breast-like flavor found in the colorful chicken of the woods mushroom. “The best way to prepare hen of the woods is deep fried in a beer batter with a side of garlic aioli. It may not be the healthiest, but it’s so good.”

Visit

Visit